Fantastic Fest Interview: Mark Romanek

One of the highlights of the fest for me was the chance to sit down with acclaimed director Mark Romanek to talk about his film, Never Let Me Go. Romanek has long been one of my favorite commercial and music video directors, having directed such classics as Nine Inch Nails’ “Closer”, Michael Jackson’s “Scream”, and Jay Z’s “99 Problems”. I found Romanek to be surprisingly soft spoken given his demanding reputation, and he was more contemplative than anyone I’ve interviewed before. I found the conversation very interesting and am including here in its entirety. If you don’t feel like reading the whole thing and just want to skip to my questions, I’ve made them bold.

Amy Curtis (examiner.com): What struck me most was the docility of the clones and how they never really fought the man, or tried to run away or fight the system. I just wanted to get your thoughts on that.

Mark Romanek: Do you think that they should have? What was your feeling about it?

Curtis: Well we all sympathize with them, so yeah I want to see them run away. Escape and do something to break the cycle.

Romanek: Why do you think that they didn’t?

Curtis: There was some kind of gentleness in them. An acceptance that that was their fate. Maybe they thought that was their purpose, so they had accepted it. But as someone who sympathizes with them and doesn’t want to see them hurt and suffering, you know, you want to see them escape.

Romanek: You know, if you ask Ishigura about this, and he is very much more eloquent than I am, he’d tell you it just wasn’t the story he wanted to write. He’s much more fascinated in his whole body of work, not just this book, in the ways that people tend not to run and rather accept their lot in life. I think he thinks it’s a more authentic idea of the way people tend to behave. He cites things like, you know, how slavery didn’t come to an end because the slaves rebelled. It came to an end because it was abolished. There’s lots of stirring stories of brave slaves who rebelled the oppressive system but he didn’t want to make that or write that story. He cites how people that receive a terminal prognosis don’t bungee jump off a bridge or climb Machu Pichu or go see the Great Wall of China, they stay in their usual routines. People stay in marriages that are abusive or unhappy. People stay in jobs that they don’t find fulfilling. And there are all sorts of practical story reasons why they don’t. They’ve been institutionalized since they were small children in a society where the fabric of that society is different than ours. They’ve been taught that it’s a priveledge and an honor to be performing this duty for society. So they don’t want to run. In a way, that’s what the film is about. It cuts to the heart of what’s different about this film and other films or other stories. It’s also a very American question, I think. Ishigura was born in Japan and moved to England when he was six. So the book is kind of a hybrid of a Japanese and British sensibility. In Japanese culture it is considered heroic to perform one’s service to the greater society and in England there is still a very pervasive class system that makes it difficult for people to rise above their station in life. So those are all the reasons why.

Gabrielle Faust (gabriellefaust.com): On that note, most people in America go through their entire lives without making a sacrifice. They don’t really know what it means to make a sacrifice or they only make sacrifices when they are placed in a position of either necessity or circumstance. Do you think that if our society possibly had a precondition that from the time we were born we knew that at this point in time we were going to be making a sacrifice, do you think that we would maybe live better lives or richer lives? Lives without regret or do think it really wouldn’t change that aspect of life?

Romanek: I don’t know. That’s a big hypothetical. I’d need time to think about it, but I do think that people in America take for granted how cushy their life generally is. It’s not cushy for everybody obviously but most people in other countries have much more challenging lives filled with more sacrifice. I don’t know. That’s just a big question. A big what if. I can only speak for myself. I just renewed my driver’s license and I didn’t tick the donor box. I didn’t do it because I don’t want to help someone in need, it’s more that I kind of feel a weird sense of ownership about myself. I guess I want to kind of control what happens even after I’m dead. I’m such a control freak. I don’t like the idea of being treated the way Ruth is treated in the film when she gives her organs and is sort of left there like a piece of meat. I guess I don’t want to be a piece of meat. A part of it probably has to do with my fear of dying. I’m sort of rambling and not really answering your question. It’s too big of a question. It’s interesting to talk about the literal story and science fiction aspects of the story but those things are really just a metaphor and a delivery system for the bigger human themes that were an interest to Ishigura. It turns the film into a parable about our predicament of having a limited lifespan and what do we decide is important when we can’t push that notion to the back of our minds anymore. I think what Ishigura was saying is that what’s important is love and friendship and treating people well.

Brent Moore (geekscape.net): One of the things that really struck me about the film is that, for all intents and purposes, it’s a science fiction film but the way that you approach that is very pedestrian. I love that these important people look like truck drivers, that kind of thing. So what was your approach to doing a science fiction film and yet making it so low key?

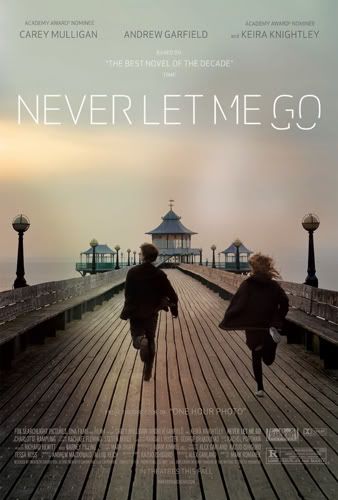

Romanek: I wasn’t making a science fiction film. I was making a love story that had a science fiction context. So the science fiction is kind of between the lines of the love story. My thinking on it was that I wasn’t making a science fiction film. I wouldn’t describe it as a science fiction film that is sort of a pedestrian science fiction film, I would describe it as a love story where the science fiction is just this sort of subtle patina on the story. The science fiction-y things that we could have done that might have been more overt like futuristic buildings or this or that gadget, I mean, they aren’t in the book. The tone you’re describing is in the book. We took our cues from the book and tried to make a faithful adaptation and capture some essence of the book. Tonally capture the quality of the book. That’s how the book tells the story. That’s not a poster for a science fiction film. But it is, and that’s what’s interesting and hopefully somewhat original about it.

Faust: While working on this film did you possibly discover something different about your own human nature? Did it maybe change your outlook a little bit on your previous perceptions of life, death, and living?

Romanek: I think any film would. Moreso maybe because of its subject matter, but making a film is such an incredible experience. It’s a marathon. It’s like some sort of boot camp on every level. It’s exhausting physically and mentally and, in this case, emotionally because the story is so emotionally fraught. It was months and months and months of travelling all over England. There are a lot of moments where you are humbled by your inability to handle something or you are cheered by the days when things seem to go smoothly. It’s a whole journey. The editing alone is a journey. I don’t think people have any real inside conception of how much work goes into making a film by so many people. So any film is going to be a process where you are going to learn about yourself. I was away from my family a lot to make the film. That felt like a sacrifice that was ironic in light of what the story is really trying to say. Which is that since our time here is so limited we have to be in the present moment and cherish our loved ones. I was away from my family out of necessity. We had just had a baby during preproduction and my wife couldn’t really travel so that was hard. That was the hardest part about it. When I could get outside of it enough to have perspective on a question like that, which happens occasionally, I would go, “God, I’m really lucky to be doing this”. They don’t let you make films like this very often and Ishigura is one of my favorite authors so I’m adapting a novel by one of my favorite authors. I can’t believe I even met the guy. There was a sense of being appreciative of the opportunity. I don’t know if that answered your question.

Jeff Leins (newsinfilm.com): There’s a few times where they are walking in these lush environments and driving through these canopies of trees and that’s juxtaposed with other times where it’s just a bleak environment. Can you talk a little bit about creating that aesthetic?

Romanek: I mean, you are pointing out one detail. I mean, we’re just following the story. I like making rules so that the crew and the team are all kind of on the same page. So we’re not all over the place, we are kind of limited. I had a limited color palette. I wanted the colors to be gentle. I didn’t want there to be strong contrast or bright colors. I felt that because the truths that the book is dealing with can be kind of disturbing but Ishigura’s writing style can be so gentle and beautiful and deceptively simple, I wanted to capture that. Part of it had to do with the palette being gentle. It’s even announced in the titles. The titles are gentle colors. I forbad the color black in the film. It crops up occasionally when it’s needed, but I felt that’s too harsh for a film about mortality. We also created these sort of meta-strategies where the first part of the film is school, the second part of the film is farm, the third part of the film is hospital. I also tried to draw out some of the Japanese quality in Ishigura’s sensibility. So there’s a simplicity to the filming and hopefully you find some resonance in simple things and an appreciation for nature and the sound of nature. Part of me just wanted the film to be beautiful because I thought the book was beautiful and I thought if the film was too naturalistic or harsh or gritty that that combined with the message would just send people screaming from the theater. I thought it’d be too much to take. It needed to be a gentle delivery of these disturbing truths.

Moore: Speaking of the book, one of the things that you hear a lot about it is the term unfilmable. So I wanted to see how you approached it and how you took to the task of adapting an unfilmable book, and do you actually believe anything to be unfilmable?

Romanek: Well I don’t think anything is unfilmable, especially these days with computers. Kubrick said that if you can think it or write it you could film it, and that was back in the sixties. But he was Stanley Kubrick. That’s a favorite quote of his. I never heard that, unfilmable. I didn’t hear it when I was reading it because no one was talking about it. I read it the week it was published in 2005. I read it and I was deeply moved and couldn’t stop thinking about it. I went back and read it again and the second time I read it I thought it was imminently filmable. I thought it was filled with wonderful images, great characters, it was not logistically demanding in terms of scale. It was boarding schools and hospitals. I didn’t think it was remotely unfilmable. I thought there was a degree of difficulty with the emotional delicacy of it and the strangeness of the tone was going to be challenging. I was challenged by that but I had a lot of help. It was a very collaborative thing. I wasn’t hired to be the auteur of this film. I was hired to take part in a collaboration with three really smart guys. Garland, Andrew McDonald, and Allon Reich who produced the film. They invited me to take part in a collaboration with them. So we all made it together really. I was the director of record, in that I made the shots and created the tone, maybe, visually. I think they did bring me in because I was thought of as a visual guy and they wanted to have a strong visual component. But I didn’t think it was unfilmable. I thought there were at least ten set piece scenes and sequences that seemed super cinematic. Also, Ishigura’s style of storytelling to me seems very cinematic because he does this sort of drip feed. He has a trick that he does that Alex Garland pointed out to me where he’ll write, “I’m about to tell you something really important” but then he tells you half of it. And then he tells you , “Ok, now I’m going to tell you something else really important” that builds on the half the thing he told you but he’ll only tell you half of that. So it really pulls you through the story and that’s good for films, that sort of formula

Unknown: Did you have any sort of challenges with filming any of the scenes with the children because there were so many children in it?

Romanek: That was probably the biggest challenge of the movie. Knowing that the first act of the film was going to have to be carried by twelve year olds, and if it didn’t work then we were screwed. If they didn’t resemble the older actors, which is something I think usually doesn’t work in films. We were very demanding that they not only be terrific actors but they very strongly resemble their counterparts. So a lot of the rehearsal time was devoted to helping ensure that that first act would be successful. I had the older actors read the first act scenes and had the younger actors observe this. It served the double purpose of the older actors gaining sense memories of having played those scenes and the younger actors, it was kind of a sneaky way to get them to see what a more experienced actor would do with those scenes. Then we mixed and matched. Carrie would play a scene with Charlie, who played young Tom. Kiera would play a scene with young Izzy, who played young Cathy. They also just spent a lot of time together playing and talking and bonding and having their mannerisms blur a little bit. We took them to the location and they just played frisbee and hide and go seek and stuff, so they got to know the layout of the school and again had sense memories of having spent time there. So that was maybe the biggest challenge

Curtis: I know the movie isn’t making a statement, a political statement, about cloning or the morality of cloning at all, but it was very muted and there with Madame and the art gallery and how they wanted to show people that they had souls. So there was a little undercurrent of that, the politics of cloning...

Romanek: It’s more present in the book. The scene where Cathy and Tommy seek out Madame and Miss Emily to try to get this deferral, more time, in the book is quite an extensive explication of all of the politics and it’s really interesting. But because we were making a film where we were really strongly emphasizing the love story it seemed like it wouldn’t be emotionally engaging. If people are connecting with the movie emotionally then they don’t want to hear all that stuff at that moment. It’s not relevant to the characters. So it’s all kind of implied and inferred. I think the idea was that the school’s campaign was because there was starting to be a public outcry of how these creatures, quote unquote, were being treated that they tried an experiment. It was an experiment to see what would happen if these human beings were treated almost like free range humans rather than battery farm humans. One of the tragedies of it, of course, the tragedy upon the tragedy, is that they didn’t really anticipate and couldn’t legislate all the emotions that would emerge in these creatures. Hence the story. But more of that is explained in the book in some detail.

Faust: Do you think maybe that was a hindrance. That they probably meant well in trying to give them some sort of solid foundation in making them fine young human beings but at the same time they were so sheltered that they had this innocence and naiveté so that when they finally did go out into the real world they were too fragile to really exist. Do you think that innocent and naiveté was a hindrance to the donors or it possibly could have been a strength in that if they stayed together and they didn’t venture too far out so they didn’t know exactly what they were missing.

Romanek: I don’t know what to say because you asked and answered the question very eloquently. I can kind of say yes. I think you’ve understood a facet of it and I agree with you. Sorry.

Moore: Kind of speaking to the love story aspect of the movie, one thing that I thought was interesting, and I’d love to get your take on it, is that it seems to imply that love was unable to save the clones and it makes the comparison to human beings. You said this was a love story and you wanted to delve into the love theme but it kind of almost comes out with a pessimistic tone about the fact that love doesn’t save you.

Romanek: It doesn’t. Nothing does. There’s nothing that will allow you to not have your life come to an end. What I find deeply moving about the film, and maybe hopeful is too strong a word, but she got what she wanted. They got what they wanted. They finally acknowledged their love for each other. That’s something that doesn’t happen in most people’s lives, even if they live to be a hundred. And they also behave with tremendous dignity, I think. They behave very well and as decent human beings. They’re not after material goods or power. They just want to acknowledge each other’s love, stay bonded in their friendship, Ruth wants to redress a terrible mistake she made and succeeds somewhat in doing that and sees some sort of redemption. What I find most moving is this graceful place of acceptance that Cathy comes to at the end of the film. We all have to figure out what our relationship to our own mortality is going to be. You can either fight against it or try to figure out a way around it like Tommy does or get plastic surgery to look like we’re not going to die. In doing my research on concepts of Japanese art and aesthetics I came across this notion called Yugen. It is the joyful acceptance of the inherent sadness of life, which is a really beautiful idea. I feel like that’s where Cathy is at the end of the film and I find that very inspiring and I aspire to have that sort of relationship with things. So love doesn’t save them, but it’s important. It just doesn’t forestall death.

Unknown: When discussing this, do you think this would appeal to a boomer age more than another?

Romanek: You know, we cannot figure out the demographic or who has responded so strongly to the film. A friend of mine just said they took their fourteen year old boy to the film who likes Transformer movies and he leaned over in the middle of the movie and said, “Dad, this is really good”. There are older literate people who read that don’t connect with it. They may be frightened by what it’s saying. There are people that cry buckets. We’ve had rave reviews that are rapturous and we’ve had people that don’t connect with it but we can’t break down the demographic of what that is. I don’t know why that is. I do know that the people that do connect with it are moved very deeply by it. That’s really gratifying.

Faust: What do you hope that audiences take away from the film?

Romanek: You know, I had someone write me an email that said “I saw your film and it made me cry and I haven’t reacted to a film emotionally like that in years and I called my father because I realized I hadn’t spoken to him in over three weeks and I told him how much I love him and how much I appreciated what a good father he’s been.” It’s just one of those reminders of what’s important maybe, and a gentle reminder I hope. Life is brief. I hope it’s more complex and nuanced than a simple Carpe Diem. It’s just a reminder of what’s really important. Friendship, love, behaving well. Those are the important things and the rest is a lot of nonsense. That’s what the book did for me so I’m just trying to transfer that.