DVD Reviews: Live Like a Cop, Die Like a Man and La Rabbia!

Following up their much-anticipated DVD release earlier this year of Fellini’s 1970 made-for-TV documentary The Clowns, RaroVideo continues to celebrate Italian heritage this month with its release of two sought-after and previously obscure examples of Italian filmmaking – Pier Paolo Passolini’s politico-philosophical documentary La Rabbia (The Anger), and Ruggero Deodato’s violent police thriller Live Like a Cop, Die Like a Man.

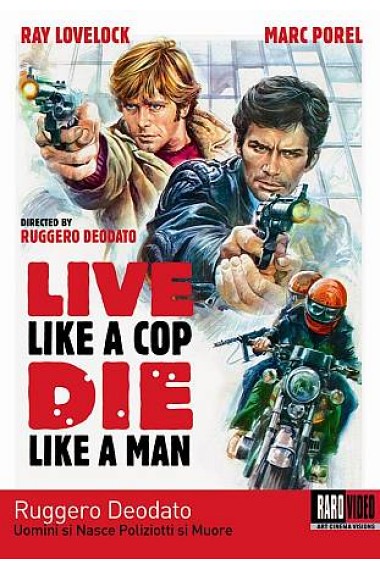

Deodato has been directing low-budget horror, action, and smut films since 1964, and is best known for his notorious 1980 film Cannibal Holocaust, which was so violent that it got him arrested in Italy for obscenity (you expect that shit from Britain, but when it happens in Italy, it’s serious). Live Like a Cop’s script was written by Fernando di Leo, and it was the last movie Deodato directed before jumping on the lucrative cannibal aborigine bandwagon in 1977 with Jungle Holocaust (a.k.a. The Last Cannibal, a.k.a. Last Cannibal World, etc., etc., ad infinitum). Like Di Leo’s Italian Connection (and pretty much every other Italian action movie made between 1965 and 1985 that doesn’t completely suck), Live Like a Cop is a noted Tarantino favorite. I anticipated something completely fucked up and insane, and Live Like a Cop didn’t disappoint me, although it’s definitely not as violent as Deodato’s cannibal movies, and I’m pretty sure they didn’t kill any giant tortoises for this one.

The movie opens with a ridiculous 20-minute chase sequence, which according to the back cover of the DVD was shot without any official authorization in the middle of the day in a crowded area of metropolitan Rome. Back at the station following the incident, the two protagonists are properly introduced. Alfredo and Antonio are members of an elite police squadron called “Special Force” which is basically authorized to do whatever the fuck it wants – kill people, torture them, fuck their sisters, destroy their property, etc., as long as it’s vaguely related to whatever case they’re working on. There’s one high-ranking Mafioso in particular named Pasquini that the boys are hoping to snatch, especially after one of their friends at the station is horrifically assassinated by two of his thugs in the parking lot.

The plot of the movie is pretty thin, but it doesn’t matter – Tony and Alfredo bust people’s heads open for 90 minutes, set a parking lot full of innocent cars on fire, scream epithets at whoever won’t give them information about Pasquini, cruise on their bikes, lounge homoerotically shirtless in their shared apartment, tag team Pasquini’s sister, shoot people without justifiable cause, handcuff some guys to the ceiling, fuck up a really volatile hostage situation, and piss off Alvaro Vitali by stealing his comic book. Plus there’s a scene with a helicopter and a really beautiful, echoey sugarpop soundtrack by Ubaldo Continiello, who did the music for several other Deodato movies as well, including Last Cannibal.

Special features include a making-of documentary, which pretty much blew my mind because they interview Ruggero Deodato and he’s just this balding guy sitting on a couch wearing glasses and a sweater vest and I guess I was expecting him to have big scary eyebrows and a beard and be glaring at you the whole time or something. There’s also a reel of commercials Deodato made before he became a filmmaker, which is neat but frustrating, because you can’t watch the commercials without Deodato’s commentary, and I’m not sure why that is. Maybe they didn’t want to pay somebody to subtitle the original audio.

Like Deodato, Pier Paolo Pasolini is most famous for making a completely vile, disgusting, notorious film. His 1975 adaptation of the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom is more overflowing with anal rape, golden showers, and forced coprophagia than probably any other movie ever produced outside of Germany. Deodato’s motivations were mainly commercial, but Pasolini had a social agenda – his version of Sodom (retitled Salo, in reference to the Fascist-controlled Republic) was set in 1940s Italy, and reworked De Sade’s systematic catalogue of depravity into a parable about the decadence and cruelty of the ruling class. Like Cannibal Holocaust, Salo was banned in several European countries and remains a controversial film today.

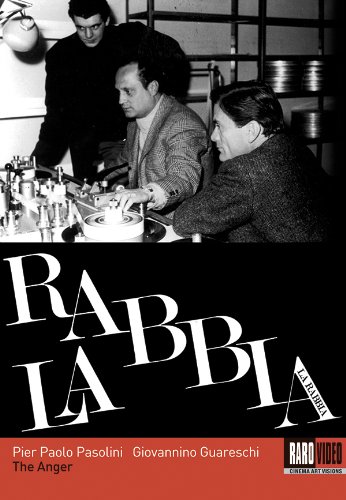

Pasolini’s La Rabbia is a composite documentary made up of re-cut footage from newsreels and other appropriated sources. The first half was made by Pasolini, the second half by Giovannino Guareschi, a right-wing humorist and political cartoonist. Technically it’s one film, but actually the two films were conceived separately – Pasolini’s film was made first, and Guareschi’s was commissioned later as a counterpoint, ostensibly to buck Italian censors who were hostile to leftist political ideology (in a supplemental essay included with the film, Pasolini bitterly opines that the producers just wanted to make more money by positing the film as a bare-knuckles debate between warring ideologues).

The most interesting thing about La Rabbia is that the presentational device for both halves is exactly the same (re-appropriating old footage and re-editing it with fresh narration to give it new meaning), and yet the style of presentation remains so radically different. Guareschi chose to approach the project as an opportunity to persuade and indoctrinate, and as a result, his half of the film, at least superficially, is more stylistically compelling and accessible. Pasolini’s approach is more intuitive, emotional and poetic, and his film is consequently more difficult to penetrate. The lack of stylistic communication between the two films could be interpreted as problematic, but seen from another perspective, it’s more revealing than the selected content of either film could ever hope to be.

The subject of the film is post-revolutionary social politics, and both approaches are essentially conservative in the sense that they express profound ambivalence about evolving social ethics and political reality. Pasolini’s film is powerful because it expresses the individual, personal relationship that Pasolini has with the issue he’s addressing – he goes off on weird tangents about things like the symbolic significance of Marilyn Monroe, or the connection between abstract art and the heavily ritualized abstraction of monarchy, as exemplified in a coronation ceremony. Guareschi, conversely, focuses on creating ironic tension between his narration and the images he’s presenting, or amplifying specific images into gross metaphors for broader ideas, like when he lingers excruciatingly on footage of the infamous Soviet dog head transplant experiments, equating their grotesquerie with the social experiment of Communism. Moments of irony like this are integrated with moments of intense, maudlin sincerity – Guareschi’s possibly unintentional counterpoint to Pasolini’s deconstruction of a coronation ceremony is a heartfelt, un-ironic presentation of footage from a royal funeral, lamenting the death of a King.

If you don’t know a lot about recent Italian political history then you might have a hard time experiencing La Rabbia at face value, but even without those vital reference points, it’s an interesting exercise in form and presentation. It’s not hard for modern viewers to pick a side in the debate – Guareschi, for one thing, is overtly and uncomfortably bigoted, and his attacks on homosexuality are particularly provocative considering Pasolini himself was persecuted throughout his life for being homosexual. The special features on the disc include an unusually in-depth and informative making-of featurette, which mainly deals with Guareschi and Pasolini as public figures, but also spends a lot of time doing nerdy academic shit like dissecting the use of color in the pieces of expressionist political artwork that Pasolini chose to sample. Some trailers and TV spots, and an earlier short film by Pasolini entitled Le Mura di Sana’a (a documentary dealing similarly with themes of social revolution), are also included.

If I had to recommend just one of these for purchase, I’d probably go with Live Like a Cop. La Rabbia is an interesting experiment, but even Pasolini was dissatisfied with it, and subsequently chose to reject montage-based filmmaking. Live Like a Cop, though its aspirations are lower and its social rebellion more sugarcoated and approachable, is an infinitely more watchable film.